Emotional context

[2]

During my first three years in Bucharest, while I was a student of the Faculty of Architecture, I lived in the same dorm room with five other students. In this small space, with little privacy, the only “holy” place, untouchable by the other roommates, was the drawing board. During this period of time, on my way back to the dorm, from the University, I used to watch the windows of the socialist collective housing units, thinking that all those people were at home, longing for the safety, the warm light, the tranquillity and the balance evoked by the shapes I could distinguish from the street. This image was always attached to the socialist collective dwellings. Never to the single family homes or the collective dwellings built after the 1989 Revolution.

The momentum of the socialist building block!

[3]

The leaders of the totalitarian regimes considered, one at a time, that they were a symbol of the last stage of human, technological and architectural evolution, so, each time, they have proposed a categorical architecture, defined by large, uniform constructions, renouncing stylistic searches, comfort or social studies. In the context of socialist realism, architecture becomes, like other arts, another instrument of dictatorship, a continuous deception of the user.

Housing development is one of the priorities of the Communist Party’s agenda, in order to maintain, as the theme-program mentions “a persisting blooming, both material and spiritual, of the Romanian people.” (Zahariade 2011, 44). Although, in the beginning of the socialist period, when the designing of the dwelling is discussed, it is taken into account both the individual dwelling and ensembles of average height, after 1958-1959, the Communist Party directs its attention, almost entirely on the problem of the housing block (Zahariade 2011, 49).

Throughout the years 1950-1989, the dwellings had to be designed taking into account, first of all, the best possible economic efficiency, thus becoming the centre of the typified design. The type – apartment – building is definitely consistent with the Party’s entire rhetoric, underlining the necessity of the equality of people, the Party being unwilling to consider any desire, aspiration or difference of the future inhabitant of the space, because all the users’ problems were considered completely solved by the way the new society was built.

The housing vertical arrangement was also conceived, besides economic reasons, as a method of social homogenization for owners, who nevertheless tried to adapt to the new limited space in which they were constrained to live. The owners, in the process of adapting to the space, started to give new meanings and functions to each room, according to their needs. The kitchen, which, although it was intended only for the preparation of food, was the centre of the house, not only for functional reasons (because of the lack of central heating, the owners had to be very creative during the winter temperatures). In the small place of the kitchen they would prepare meals, often eat them, gather with their friends for a coffee and sometimes a small bed will be placed for the situations when one member of the family had to rest. Before the 1989 Revolution the kitchen was preferred to the living room for family and friends meetings. Most of the times, the closet became the father's repair shop/ mother’s cellar, full of jam and pickles jars, or in some cases was demolished to gain more space. The bathroom could be transformed into a hairdressing salon for acquaintances, a laundry/ drying room while the space of the service sanitary group was used as an improvised dark room or was simply abandoned when there was a need for a second closet.

Home of a child raised with a key around her neck

[4]

Home means, in my case, the sharp sound that the old wooden door of my grandfather’s apartment was making, every time it opened. The entrance to the two-room apartment could be done by applying a technique known only by the occupants, namely by concentrating the entire weight of the body into the right shoulder, with which you would give a firm push to the door. My grandfather, the former army colonel, with a rigid education and then occupation, waited for me, every day, to get back from school, in the kitchen, with his wide smile, watching over my lunch, carefully prepared by him. At that time in my childhood I was stubbornly eating only a single dish, hot-fried cabbage, with a small piece of pork meat and polenta. And that was it. My grandfather asked me every day, what would I like to eat, prepared, after my grandmother’s death, to cook anything for his granddaughter, in his small and modestly equipped kitchen. My answer was, invariably, the same.

Nostalgia/ Going back in time in the type – apartment – building

[5]

When I decided to rent the apartment in the collective housing unit, where I have been living for the last five years, I realized that I would live in an apartment that had the same partition as my grandfather’s home. But only after I assumed the role of the architectural space’s detective, after discovering the lost letters in front of my collective building block, I had a few moments in which I strongly felt the connection between the two spaces. One of these moments happened on some day when I walked into my apartment, preoccupied with the projects I wanted to finish that day. I heard a noise, probably made by one of my many neighbours, who resembled to the sound of my grandfather’s old wooden door, which will remain imprinted, in my mind, until the day I die. I kept my eyes closed for a few minutes, trying to stay as long as possible in that little portion of the past, so alive at the time, that if I travelled back in time, my grandfather would welcome me, in his warm and funny way. He would leave his favourite volume describing Winnetou’s adventures on the white cupboard, he would ask me how my day went, if my schoolbag was as heavy as yesterday and finally would let me know that we are going to have freshly baked donuts (the only dessert that he could actually master). As soon as I would finish my meal, I would have gone for a walk in the small patch of garden that unfolded under his balcony. I would have smelled the lilies of the valley, which I imagined smelled like my grandmother, which I was too young to remember, I would have been amazed by the five tomatoes grown in the two rows planted by him and I would wonder at the snails “growing” at the base of an old poplar, caressing, on my way out, the fir tree, which my grandfather brought back, from a mountain holiday, in his backpack.

Buildings’ stories

[6]

The house starts living along the one who inhabits it, thereby constantly gaining a new meaning with every transformation it goes through. In the end, the resulted space will be able to explain the way its owner lived. When those who inhabit it cease to exist, the space also goes through a process of extinguishment. The way we read the space of a building and understand the stories that helped shape it, can’t be directly related to a minimum range of time or an optimal path. The space will be covered sequentially and the reading can start from any point of the building, either from the site on which it is located, or from the part of the town it belongs to.

The way in which the architectural object is located in the territory represents, as Mircea Eliade mentions, in The sacred and the profane, an assumed gesture of creating a world in which we decide to live. The home is considered a holy realm, being defined as imago mundi (its connection to the Cosmos is being made by the projection of the four cardinal points, starting from a central point, in the case of a village, or by designating an axis mundi, in the case of family dwellings, thus linking Heaven to the Earth), the world also being a divine creation (Eliade 2013, 33). The architectural object has a strong connection with the site, the piece of earth from which it is born, being modelled in such a way that it takes into account its attributes, Heidegger announcing that “ Therefore, spaces get their essence from places and not from the so-called space” (Heidegger 1995, 185). There are no two identical sites, therefore, from this point of view, the idea of collective housing and even more, the concept of typified design is strongly flawed.

Architectural detective work in a type – apartment – building

[7]

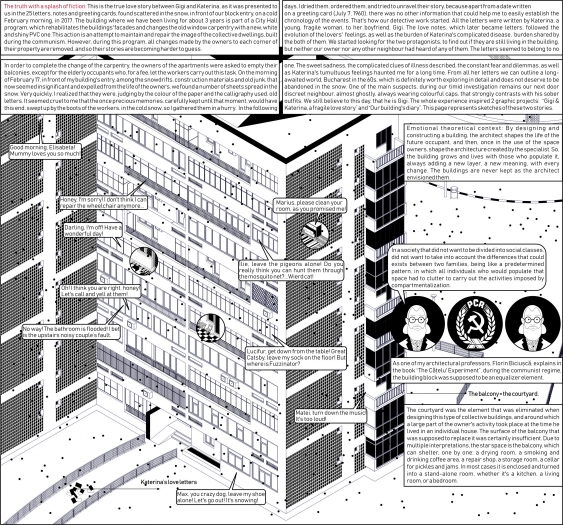

Taking into account the advantages of the flexible hybrid graphic medium of comic strips, which combines, in their structure, the narrative element, space and movement and has always had a strong connection with the notion of architecture, which in some cases is a symbolic protagonist or even centre of the comics’ story, another fellow architect and I, decided to illustrate the analysis of the community of the 10 floors apartment building. Built in 1968, with seven staircases, the analysed collective housing unit is situated at the intersection between Câmpia Libertății and Baba Novac streets. Each staircase sums a total of 44 apartments.

We conducted the graphical analysis of the building before it passed through the process of rehabilitation of the facades. We have been living for more than 3 years in our type –apartment – building, when it was chosen to take part in the City Hall program, which rehabilitates the buildings’ facades and changes the old window carpentry with PVC ones. This action is an attempt to maintain and repair the image of the collective dwellings, built during the communist period and, also, to increase the energetic efficiency. However, during this program, all the small changes made by the owners to their properties are removed, their stories becoming harder to read.

Another example of individual and collective adaptation to the limited space of the apartments, the balcony, which receives many interpretations in the socialist building block, also offered, when analysing our building, many interpretations: a wide range of materials and colours of the carpentry used to close the balcony’s space, a multitude of coloured curtains used to decorate it, a generous number of flowers in pots, so often watered and carefully cared for by hardworking housewives, who were dusting everything, including the exterior air conditioner unit, proofs of the passing fashion of exiling part of the kitchen’s appliances, especially the cooker and stove, a storage space for old furniture and other items. There were also a small number of tenants who decided not to interfere with the way the space of the balcony was envisioned by the architect, keeping it open, and often furnished with beach umbrellas and lounge chairs. Each of these interpretations tells a story, each of them offers clues about the ones who inhabit the apartments.

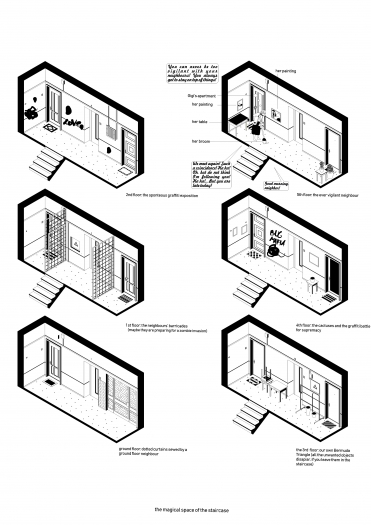

The staircase, which in Vintilă Mihăilescu's article, The building block between place and habitation, is symbolically called „no man’s land”, in the case of our building the space of each floor is interpreted in a different manner, according to the owners of the apartments. The over suspicious residents living on the first floor decided to barricade themselves behind metal grills, separating their apartments from the rest of the staircase. On the fifth floor, a retired lady, with a strong passion for cactuses, decided to share, with the rest of the tenants part of her collection, placing six cactuses of different shapes and forms on the hall in front of her apartment, while also being the main “suspect” for the “beautifying” of the elevator mirror, using a picture frame with intricate decorations. The four member family on the 7th floor considers the staircase space as an extension of their apartment, because they are always leaving half of their pairs of shoes in front of the door. Of course, we also had groups of young people, eager to take refuge from the cold weather, sharing a beer and trying out their artistic talent, not yet thoroughly exploited, on the white walls, freshly painted by the administration, while sometimes listening to music. The staircase space also has a mysterious feature, being a distant relative of the Bermuda triangle, in which neighbours deposit the objects they want to part with and almost immediately one of the other neighbours finds a place and use for the old table, chair, old paintings or disks. It is a silent agreement between the ones that offer and the ones that receive.

Each apartment entrance has a door mat, thus creating a complex collection, containing: cuts of different shapes of expensive Persian carpets, now expelled from the space of the apartment, various drawings of flowers, mice and geometrical patterns, wishing us ‘welcome’. The staircase space is also where short encounters between neighbours take place, in which even we, the so-called intruders, who pay rent, symbolically named by permanent tenants “the newcomers” get to take part in the small community’s events. There is always a retired lady, very vigilant, who seems to have a strict journal, logging every move made by each tenant, the neighbour who is convinced that you were determined to cause a flood in his apartment, the retiring neighbour who comes out every day to make small repairs to his car, always worried that the wind will push your motorcycle over his car, a multitude of cats and dogs that offer the opportunity to have a warm conversation in the elevator, with walls full of love declarations, written with markers, by a young, artistic and very much in love couple.

Investigating the built space of a collective socialist housing unit, using 49-year-old letters

[8]

On a 2017 February morning, in front of my building block’s entry, among the snowdrifts, construction materials and old pieces of furniture, we found a number of sheets of paper and, judging by the colour of the paper and the calligraphy used, I realized that they were old letters. It seemed cruel that once precious memories, carefully kept until that moment, would have this end, swept up by the boots of workers, in the cold snow, so I gathered them, dried them, put them in order and I tried to understand their story. It was a difficult task, because, apart from a date written on a greeting card (July7, 1969), there was no other information that could help me to easily establish the chronology of the events. All 25 letters, notes and greetings were written by Katerina, a young, fragile woman, to her, then, love interest, Gigi, following the evolution of the lovers’ feelings, as well as the burden of Katerina’s complicated disease, burden shared by the two of them.

The story behind the letters can walk the reader through diverse architectural settings: the little shoe repair shop, where they decided to start their first date, the cinemas they went to, the polyclinic where Katerina went to much too often, trying to solve her medical issues, the shop in which they both work, the train station where she waits for her mother, who comes to take care of her poor health and finally, her bedroom, where she falls asleep every night, with Gigi in her mind, not before writing him a new letter or little note. We decided to try to search for the two protagonists and to find out if they are still living in the building, so we could return the letters to them, but neither the owner of the apartment which we live in, nor any other neighbour had ever heard of their names. The letters seemed to no longer have owners. The sweet sadness, the complicated clues of the illness described in each page, her constant fears and dilemmas about the way her life will turn out, as well as Katerina’s tumultuous feelings, haunted me for a long time. From the story composed by the letters we can gather architectural, social and medical details about the way Bucharest presented itself in the 60s, which is definitely worth exploring and does not deserve to be forgotten.

During the investigation for the letters’ owners, which then led to an architectural investigation of the different spaces contained in our building block, one of our “main suspects, remains our next door discreet neighbour, always wearing colourful caps, which strongly contrast with his sober outfits. We are still convinced, to this day, that one of his names or even nickname is Gigi.

Overlapped fragments of life in the type – apartment – building

[9]

One morning, in the autumn of last year, while I was having breakfast in the cold kitchen, I heard loud noises, coming from Gigi’s apartment, on the background of a news cast lady, who was screaming aggressively, through the far too thin, dividing wall. His son was knocking continuously on the door of the apartment and at the same time calling him on the phone, trying desperately to persuade his father to open the door. You can only hear rhythmical sounds and his irritated voice, repeating without stopping: Open! I’m at the door. I am the one knocking!

The old man answered the phone, but he was not convinced. He remained in his world, locked in the house, with the soundtrack of endless stream of commercials on the background.

This moment reminded me of the many episodes, strikingly similar, between my grandfather and my mother. Between me and my grandfather there was always a complicity, an alliance, which I kept intact until the day he died. I just think I fully understood him. It often seemed to me that only I understood the frustration he felt, being treated after a long military career as a helpless child. Maybe this happened because I was a kid and the world treated us the same way. But, towards the end, there were many moments when I felt that he was travelling at another speed, to places I was not allowed. I like to think that, in such moments, when everyone believed he was completely disconnected from reality and helpless, he actually decided it was time to take a break and to escape into a world of his, secure, full of amazing memories, a little selfish, a bit mischievous, looking with amusement at my mother’s effort to get to him. I imagined he punished her, with a grim smile, not answering the door, for all the moments when, being a child, she did not eat all the vegetables in the soup, she did not finish her homework in time, or because she returned home with her stockings, considered overly precious during the communist period, torn on her knees. I found myself smiling in the middle of the kitchen, imagining Gigi was childishly punishing his son, for breaking the neighbours’ window, for colouring with markers on his favourite crime novel, or for the moments he lied, solemnly promising that he would not play on the building site, near their

building block. I like to think he chooses to do that and he’s having a lot of fun. Just like my grandfather used to do.

Some kind of conclusion

[10]

Although we considered that the process of architectural investigation of the space we live in, which started 3 years ago, turned us into fine connoisseurs and observers, during this period of retreat in our houses, we still discover new layers and meanings. Once we burned through the stages dominated by fear, revolt, exhaustion and tense stoicism, alongside the inhabited space, our feelings gradually transformed into ones of understanding, camaraderie and mutual care of two entities going through the same war. I feel so grateful for the 10 meter long balcony, which in the absence of my running sessions, I try to walk at least 10.000 steps a day, glad that if I sit on the couch or in bed I can see the sky, thanks to the vicinity of the building block to a park, delighted to discover, in the imperfections of the apartment, fragments from other lives spent in this space, which urges me to put together all the information discovered, but, also, easily transports me to my grandfather’s apartment. There are still so many stories to discover.

So, I am currently living and spending the self-isolation period in one of the most controversial and less appreciated constructions of Romanian architecture, buildings which will always be the memory of an immense wound produced by the totalitarian regime. But with whom I will always feel deeply bounded.

References:

Bachelard, Gaston. The poetics of space [Poetica Spațiului]. (I. Bădescu, Trans.). Piteşti: Paralela 45, 2003.

Dumitrașcu, Gențiana. My building block. A sequential architectural story, Arhitext (October 2019).

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and The Profane [Sacrul și profanul]. București: Humanitas, 2013.

Heidegger, Martin. The Origin of the Work of Art [Originea operei de arta]. București: Humanitas, 1995.

Robinson, Sarah. Nesting: Body, Dwelling, Mind [A-ți face cuibul: trup, casă, minte], Arhitext Design Foundation Pulishing, Bucharest, 2019.

Mihăilescu, Vintilă. The building block between place and housing [Blocul între loc și locuire], Revista de Cercetări Sociale, 1/1994 (June 1994).

Mihăilescu, Vintilă. The house and the road. Gaston bachelard and the reveries of the house [Casa și drumul. Gaston Bachelard și reveriile casei], Arhitext 1/2017, (January 2017).

Zahariade, Ana Maria. Architecture in the communist project. Romania 1944- [1989Arhitectura în proiectul comunist. România 1944-1989]. București: Simetria, 2011.